Fighting the fentanyl crisis

By Beth McKay and Laura King

Features Hot Topics PreventionNo one signs up to be a firefighter to do what crews in Vancouver’s downtown east side do every day: administer lifesaving anti-overdose drugs to opioid users – sometimes several times a day and sometimes to the same user twice in one shift.

No one signs up to be a firefighter to do what crews on Vancouver’s downtown east side do every day: administer lifesaving anti-overdose drugs to opioid users – sometimes several times a day and sometimes to the same user twice in one shift.

No one signs up to be a firefighter to do what crews on Vancouver’s downtown east side do every day: administer lifesaving anti-overdose drugs to opioid users – sometimes several times a day and sometimes to the same user twice in one shift.The conditions are sordid – filthy alleyways and flophouses – and the system flawed; users keep using, knowing firefighters or paramedics will revive them.

Vancouver’s Fire Hall 2 was already a busy station – 600 calls a month. But with the rise in fentanyl use, firefighters in November responded to a record 1,255 calls, of which 735 were overdoses, according to a city press release.

Although management in Vancouver says it recognizes the challenging working conditions, firefighters say the issue is bigger than the department can handle, and they want Ottawa to implement a national strategy to tackle the opioid problem.

That solution is long-term, at best; in the meantime, Vancouver’s firefighters – and management – want more resources to help prevent stress and burnout, and give firefighters back the time they need to train. In early December, Vancouver city council was considering a request from Fire Chief John McKeaerney for an additional rescue truck,16 full-time firefighters for Hall 2, and a full-time mental-health worker, at a cost of about $1.8 million a year.

McKearney said a proposal back in July for a two-crew rescue unit to deal with growing call volume and other suppression-staff responsibilities, such as inspections and enforcement of six-storey wood frame buildings, vacant homes, and hoarding, was “not wholly supported” by council.

“But when tsunami hit with fentanyl,” McKearney said, “I increased it to three-person unit because of the type of evolutions that type of responders have to do when dealing with an overdose case.

“The most recent ask or position by the corporation for council to consider is a direct result of the opiate overdoses.”

McKearney said the department and the city are developing initiatives to deal with fentanyl but there’s no short-term solution.

“We’re in discussions ongoing with Vancouver Coastal Health reps, and certainly we’ve had [Health] Minister [Jane] Philpott out here, and number of different federal representatives. Everyone is certainly aware of the crisis – it’s almost epidemic. But there is still disclarity about how to stem the tide.

Vancouver’s initiatives – supervised injection sites, literature that speaks to young people about the dangers, and free naxolone kits – are being replicated in other cities where fentanyl is turning up.

“But as far as how to stem the tide,” McKearney said, “that’s a pretty tall order.”

McKearney says crews are rotated out of Fire Hall 2 sooner than other halls, but agrees that the conditions and frequency of responses to overdose calls are straining firefighters and department resources.

According to the union, back in the 1980s, Vancouver Fire and Rescue Services had about 160 front-line firefighters on duty at any time. Today, there are 132. Like other cities, Vancouver has been a victim of finicky taxpayers, tight budgets and resource reductions.

“In 2010, the city commissioned a study on the fire department,” said union vice-president Dustin Bourdeaudhuy. “That study recommended to increase fire resources in the city, and since then we have had a cut.”

To offset the workload, medics are sometimes brought in on Friday and Saturday nights to help with the call volume, but Bourdeaudhuy said the relief is inconsistent.

In Winnipeg, where fentanyl use has surged in the last year, union president Alex Forrest says the issue is more manageable.

“We’re all paramedics,” Forrest said of Winnipeg’s firefighters. “I do know that Vancouver’s firefighters are very under staffed as compared to other major cities across Canada, and that could be part of the issue.”

Safe consumptions sites could be part of the solution to the fentanyl crisis and Vancouver Coastal Health wants Ottawa to make it easier for communities to establish these locations. Philpott met with Vancouver firefighters Nov. 10 and said legislative changes for safe consumption sites are under consideration and will be announced in the near future but offered no specifics.

“It’s long past time we all come together to do our part to respond to this,” Philpott said.

“One single change to legislation is not going to fix the problem. We need to make sure we look at the big picture.”

International Association of Fire Fighters Local 18 representatives Chris Coleman and Lee Lax were invited to speak to an all-party House of Commons committee in October, and discussed the reality for Vancouver’s frontline workers – highlighting the strain that the fentanyl crisis puts on training, education, and the mental well-being of responders.

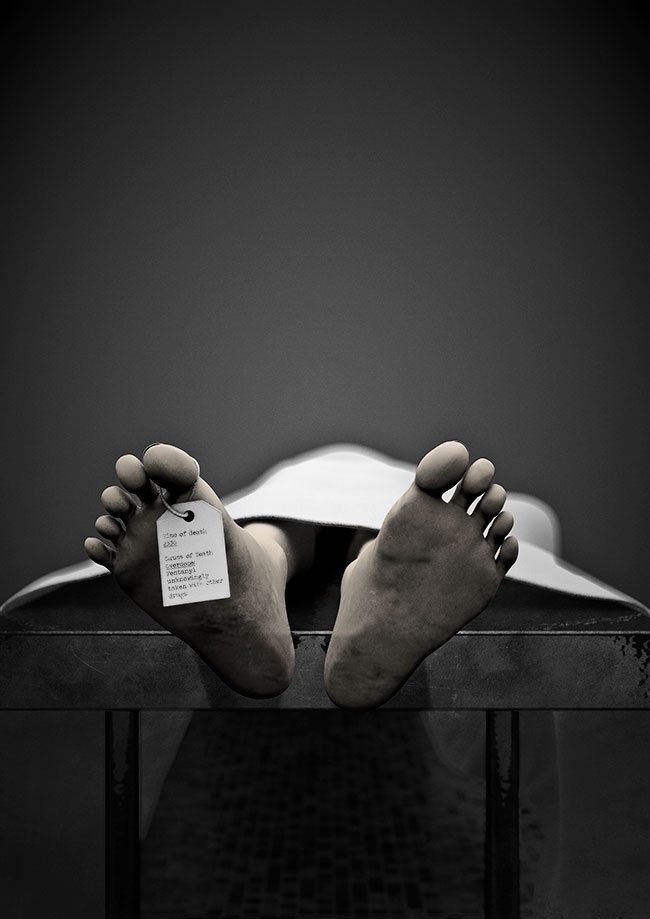

Coleman offered some numbers to put the situation into perspective; according to the B.C. Coroners Office, Coleman told the committee, the percentage of illicit drug deaths in which fentanyl is involved rose to 60 per cent in 2016 from 30 per cent in 2015 and five per cent in 2012.

“This is moving in the wrong direction,” he said.

Coleman explained to MPs that firefighter training and public education have taken a back seat. McKearney also emphasized that with the increased workload, other types of work, including training, are difficult to fit into the daily regimen. Bourdeaudhuy agrees.

“At the downtown east side, it is impossible for them [firefighters] to get any training done,” Bourdeaudhuy said. “They are overwhelmed.”

Bourdeaudhuy works at Fire Hall 20 but served at Hall 2 four years ago; he said the station had a high call volume when he worked there but it was nowhere near today’s levels.

When dispatched to a fentanyl-overdose call,

firefighters in Vancouver use Narcan, an intramuscular injectable form of the opioid-reversing drug naloxone. Coleman explained that this medication can revive patients in as little as 20 seconds, but it can sometimes take multiple attempts.

In early October, a nasal version of naloxone was approved for British Columbia’s first responders to carry; it works similarly to the injectable drug. First responders in Quebec already use the nasal spray and Réjean Leclerc, paramedic and president of the Syndicat du préhospitaller, told the House of Commons committee that this method works quickly, but the patient needs to be closely monitored following administration. Leclerc noted that training to administer the drug can take up to four hours.

McKearney said in an interview in October that firefighters had not yet used the nasal version of naloxone. “There hasn’t been a lot of time spent exploring this [in Vancouver],” he said, adding that firefighters need to get the appropriate training, “but with the increased workload in the hall, it’s challenging to keep up.”

While regular firefighter training is taking a hit because of the time crews spend responding to fentanyl calls, the health and well-being of firefighters is also in jeopardy. Coleman emotionally explained to the House of Commons committee that regularly seeing such helplessness and suffering is difficult for first responders.

“There is a physical and mental strain in the sheer volume of responses, which ultimately affects a firefighter’s ability to recuperate between shifts,” Coleman said. “In conversations with these firefighters, I hear a lot of ‘It’s driving me nuts,’ ‘I can’t take it.’ I’m told stories about being in an alley with 20 or 30 drug users, they’re [firefighters] unprepared, and untrained for that.”

Like Coleman, McKearney discussed the importance of mental health, explaining one of the most troubling issues for firefighters on the ground is seeing the same overdose patients repeatedly, sometimes during the same shift.

Hall 2 firefighters say post-shift recovery is difficult because of the stress that everyone brings home. Falling into a regular sleep cycle is challenging because firefighters’ minds are always on the job. More firefighters are booking off on stress leaves. In addition, firefighters are frustrated; addicts know they can use because they are aware Narcan is readily available and that someone will likely help them if they overdose. “Being immersed in an environment like this, it feels hopeless,” one firefighter said in an interview.

During the all-party committee meeting, Conservative MP Colin Carrie asked if naloxone is really the solution or just a small band-aid on a big cut? Coleman told the committee that naloxone doesn’t prevent overdose deaths, first responders do. So the question remains: What needs to be done?

“We need to realize that this is as much a mental-health emergency as it is a drug emergency,” said Lax, the other firefighter who also attended the committee meeting.

“They [fentanyl users] turn to opioids to relieve them from the stress of their mental illness.”

Firefighters want MPs to help tackle the issue, beginning with supplying basic needs, such as housing, for those living on the streets.

“This crisis,” Bourdeaudhuy said, “is way beyond the fire department’s control.”

What is fentanyl?

Fentanyl is a synthetic opiate narcotic, a prescription drug used primarily for cancer patients in severe pain. It is 50 to 100 times more toxic than morphine.

Print this page