Volunteer response

By David Payzant

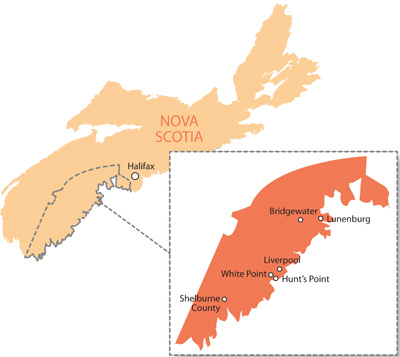

Features Hot Topics Incident ReportsOne hundred volunteer firefighters from 16 departments responded to a blaze at the White Point Beach Resort at Hunt’s Point on Nova Scotia’s South Shore on Nov. 12.

Editor’s note:

One hundred volunteer firefighters from 16 departments responded to a blaze at the White Point Beach Resort at Hunt’s Point on Nova Scotia’s South Shore on Nov. 12. David Payzant, the deputy chief in Liverpool – the first responding department – was on scene and explains the response and the challenges of fighting a raging fire in an 83-year-old wooden building. The main lodge, which housed 15 of the resort’s 159 guest rooms, the kitchen, dining room, a great room, meeting rooms and an indoor pool, was destroyed. White Point (www.whitepoint.com) announced on its website on Dec. 9 that it will rebuild and will reopen in the fall.

|

|

| Early-arriving crews gear up and prepare to fight the intense blaze at the White Point Beach Resort on Nova Scotia’s South Shore on Nov. 12. Photos by Tammy LeBlanc

|

At 14:24 on a beautiful fall afternoon, members of the Liverpool Firefighters Association received a call to respond to 75 White Point Road, #2, for a confirmed structure fire at the main lodge at the White Point Beach Resort, just outside Liverpool.

Liverpool firefighters quickly responded with one pumper, two tankers, an aerial ladder, a rescue, a utility and command vehicle, and Fire Chief Steven Parnell quickly advised dispatch to begin the process of one of the largest mutual-aid responses in recent memory for the Liverpool Fire Department, with 16 departments at the scene and another five providing coverage. (Twelve departments responded to a fire in June at the historic Fairview Inn in nearby Bridgewater.)

|

|

White Point is perched on the Atlantic Ocean on a picturesque strip of Nova Scotia’s South Shore, about 90 minutes from Halifax. The main lodge houses 15 rooms, the kitchen, dining room, meeting rooms and an indoor pool. Rustic cabins dot the property and newer beach houses sit on the shore. The White Point Estates community of homes and the Ocean Club condo development are fairly new additions.

The main lodge at White Point is 83 years old and was not sprinklered. The building had working smoke alarms. The lodge is set back from the highway and is accessed by a narrow road that meanders through the property.

Fire departments in Nova Scotia’s Queens County have strong mutual-aid agreements under which departments that require specialized equipment or extra manpower from another department can request to have that equipment or personnel respond to another jurisdiction. Chief Parnell requested tankers and manpower from the North Queens Fire Association, Greenfield, and the Port Medway Fire Department. Following his arrival on scene, Chief Parnell quickly realized that more help would be required. Parnell has been the volunteer chief in Liverpool for seven years. Liverpool has seven vehicles and 40 members.

Fighting a monster

The fire originated in the basement of the main lodge in the 83-year-old resort – it was noticed by an employee. Upon arrival, heavy smoke was venting from two basement doors on the eastern end of the building. The smoke was under considerable pressure and appeared to be driven similar to a jet engine as it blew through the open doors and to the outside. Chief Parnell requested a second ladder truck and a pumper from Bridgewater in neighbouring Lunenburg County, a pumper, tanker and rescue from Lockeport in Shelburne County, and tankers from Italy Cross and Shelburne.

|

|

| Crews attempted to enter the basement of the 83-year-old wooden structure but were forced back by smoke and heat.

|

Liverpool firefighters made entry into the basement area of the lodge – eight people on different teams at different times – but, after several attempts, were driven back by intense heat. With the arrival of mutual aid, alternative methods of entry – from the other end of the building – were attempted but to no avail.

Chief Parnell and his two deputy chiefs were faced with a new challenge: how to efficiently organize and use the assistance offered by the mutual-aid departments? Chief Parnell assumed the role of incident commander and each deputy assumed responsibility as a sector officer, taking command of a particular side of the structure.

Responding chief officers from the mutual-aid departments were assigned to assist the sector officers from Liverpool, and were also assigned a side of the building by Chief Parnell. Therefore, each side or sector of the building had two sector officers – one from Liverpool and a chief officer from a mutual-aid department.

Two captains, both from Liverpool, were charged with establishing a working water supply; one captain was stationed at an area for tankers returning from a water supply where a pumper filled the empty tankers at a hydrant two kilometres away. The second captain was stationed on the fire ground and called for full tankers, one at a time, to approach the scene from the staging area, where they dumped their loads of water and returned to the hydrant for filling.

A staging area was set up to manage all firefighting personnel, especially interior firefighters who were wearing breathing apparatuses (once the fire fight went defensive and the building was surrounded with hoselines, not everyone wore BA). Also, a rehab area was set up by paramedics from Liverpool and EHS staff from several other South Shore paramedic bases. RCMP helped staff from White Point evacuate patrons from all of the cabins and other buildings on the lodge property to a safe area. (All patrons and staff had been safely evacuated before firefighters arrived on scene.)

The blaze progresses

With intense heat and a fast-moving fire, interior crews were forced to retreat when the fire caused structural collapse and began to extend into the main floor area, which contained a dining room and a kitchen area.

Chief Parnell decided to set up defensive operations in order to protect exposures on the property that were close to the main lodge. Within a short time – probably 15 to 20 minutes after arrival – almost the entire basement and first floor were completely engulfed in flames. Both aerial ladders from Liverpool and Bridgewater were positioned to prevent the fire from spreading to the opposite end of the building, and handlines were deployed around the perimeter of the structure to try to contain the fire.

By this time, the fire had extended into the second floor and almost the entire building was being consumed by flames.

As the firefighters on scene continued to contain the blaze, and fatigue became an issue among personnel, further mutual aid was requested. Crews from Lunenburg were dispatched to respond with a pumper, a tanker, and a rescue; Sable River responded with a tanker and personnel; Mahone Bay and Charleston were dispatched with pumpers, and two other departments – Barrington, and Island and Barrington – answered the call with a rescue and personnel.

Getting control of the fire

With the main lodge engulfed in flames, the structural integrity was compromised to the point at which the floors collapsed on top of each other and, eventually, the remains of the lodge ended up in the basement.

|

|

| The floors in the main lodge pancaked and collapsed into the basement, causing fire to be trapped between the floors and necessitating heavy equipment. Photos by Tammy LeBlanc

|

That created yet another problem: fire trapped between each floor and all piled with the remains of the foundation. To fix this, and to allow firefighters to safely allow access to extinguish the fire, an excavator was brought to the scene and dug what was left of the lodge in a fashion that ensured the area in which the fire was believed to have originated was not touched. However, with the volume of fire in that area, that too had to eventually be brushed aside by the heavy machinery.

Response challenges

A fire of any size can pose its share of challenges. Across North America, when firefighters are en route to any fire scene, they must consider several factors that can determine the course of action to properly deal with the fire, the victims, and the responding personnel.

|

|

| While there were challenges fighting the blaze at the White Point Beach Resort and the main lodge was destroyed, the mutual-aid and incident-command systems worked well and allowed firefighters to save the other buildings on the ocean-side site.

|

Building construction – The main lodge was constructed 83 years ago. It consisted of heavy timber and wood-frame construction and no sprinkler system was present in the building.

Occupancy – At 14:24 in the afternoon, the lodge was full of patrons and staff. With several dozen people in the building at the time of the fire, everyone was evacuated from the building before firefighters arrived on scene.

Water supply – With a decent supply of water nearby, the availability of water was not the issue; however, setting a system up under which tanker trucks could provide a steady and smooth transition from the staging area to the fire ground tended to be a major hurdle.

Street conditions – The main road to the resort is narrow – two vehicles cannot pass at normal speeds. The road also contains several speed bumps, which means slow-moving vehicles. The staging area for tankers was set up at a crossroad just outside the main lodge. This was done when enough tankers had arrived on the scene that there was a bottleneck of fire apparatuses. Thus, the staging area was set up to ensure an organized and even flow of trucks as they accessed the scene.

Weather – The weather on Nov. 12 was beautiful. However, there were light winds blowing, which created problems with smoke being swept across an area where there were other cabins and facilities, causing an evacuation of those areas.

Exposures – With a fast-moving and major fire sweeping across the main lodge, it became evident that nearby cabins and halls may need to be protected. Aerials from Liverpool and Bridgewater were positioned to prevent the flames from reaching that end of the building. Handlines and monitors were also deployed between the main lodge and the exposures in an effort to prevent the fire from spreading.

Although the main lodge was destroyed, more than 100 volunteer firefighters joined forces to efficiently maintain control of and extinguish a fast-moving fire – 100 normal, everyday people who share a passion for serving their communities and who spend countless hours training for that once-in-a-lifetime fire. Most importantly, due to well-trained staff, no one was trapped or injured, including the world-famous bunnies that inhabit the resort grounds.

The White Point incident will serve as a training aid and its facts and stories can and will be shared for years to come.

| The response Sixteen departments were on scene:

Five departments provided coverage:

Four dispatch centres

|

David Payzant is the deputy chief in Liverpool, N.S., a volunteer department on Nova Scotia’s South Shore with seven vehicles and 40 members.

Print this page