Reducing exposure

Lauren Scott

Features Health and Wellness WellnessThe Hamilton Fire Department in southern Ontario responded to a challenging fire at St. Peter’s Hospital last November.

Asbestos is a carcinogenic mineral that was commonly used in building construction The Hamilton Fire Department in southern Ontario responded to a challenging fire at St. Peter’s Hospital last November.

Asbestos is a carcinogenic mineral that was commonly used in building construction The Hamilton Fire Department in southern Ontario responded to a challenging fire at St. Peter’s Hospital last November.After the incident, Fire Chief Dave Cunliffe told CBC News of the difficulties members faced fighting the hospital fire. Firefighters had to climb the stairs on their knees, hose in hand, to try to push back the fire, he shared.

“The fire was literally rolling down,” Cunliffe said at a press conference following the fire. “It was a very difficult fire, no question about it.”

Ninety-six palliative care patients were forced to relocate to other hospitals in the city and in nearby Burlington, Ont.

But the challenges did not end once the fire was put out.

After the incident, firefighters were extremely cautious during the decontamination process because the building contained asbestos.

Asbestos and firefighters

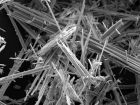

Asbestos is a carcinogenic mineral, known to cause cancer that was commonly used in building construction, insulation, cement, automotive parts such as brake pads, and even firefighter gear for its heat resistant properties.

Asbestos can be found in many buildings built before the 1980s, though it is rare to find the mineral in modern homes.

Paul Demers, an occupational health professor at the University of Toronto, says firefighters should assume asbestos is present in older buildings.

“The challenge is that almost any structure built prior to, let’s say about the mid-1970s, probably has asbestos in it somewhere. We used a lot of asbestos in Canada until around that time,” Demers said.

He says firefighters need to be cautious around insulation, pipe wrappings, linoleum, plaster (asbestos is often found in popcorn ceilings), and even some doors, when responding to older homes.

“The best case scenario is that [the asbestos] remains inside of those materials and it doesn’t get into the air,” Demers said. “The problem is that when there’s a fire it’s very easy for some of that to be released into the air, because it survives the fire.”

“Once it’s been released it’s going to be back in the environment.”

Firefighters who work in cities with a large number of older buildings, like Hamilton, Ont., are particularly vulnerable for asbestos exposure.

“In a way, you almost have to assume that if a building is in that age group and anything older, unless you know differently, there could be asbestos there.”

Asbestos -related cancer

When asbestos is released into the air, firefighters are at risk of breathing in the fibres. Once inhaled, the fibres can imbed themselves into the lining of the lungs or chest wall, causing mesothelioma – a rare but highly fatal form of cancer caused by asbestos exposure.

Mesothelioma and asbestos-related lung cancer can take 10 to 40 years to develop, as symptoms – such as painful coughing and shortness of breath – may not appear until the cancer has spread. Many patients are not diagnosed until later stages, which negatively impacts the chance of survival.

The average life expectancy following diagnosis is about six to 12 months and 67 per cent of people die within a year according to the US-based Mesothelioma + Asbestos Awareness Center.

A 2013 study published in Occupational and Environmental Medicine found that firefighters are two times more likely to develop mesothelioma than the rest of the U.S. population, as they are more likely to come into contact with asbestos.

In fact, firefighters are 100 per cent more likely to be diagnosed with mesothelioma than the general population, indicates a 2015 study that looked at firefighters working in San Francisco, Chicago and Philadelphia. Another study found that older firefighters are 159 per cent more likely to develop cancer than the average American, as they have had greater exposure to older homes.

However, Demers said there is still not enough data linking firefighters to increased levels of mesothelioma and asbestos-related cancer, as these diseases take such a long time to develop and track. He says he expects more firefighter-specific research in the coming years.

Asbestos fibres were linked to 1,900 lung cancer and 430 mesothelioma cases in Canada in 2011, according to the government.

In 2016, the Canadian government announced that the country is expected to completely ban asbestos by 2018, implementing new codes and regulations.

The proposed Prohibition of Asbestos and Asbestos Products Regulations, introduced in January, “would prohibit the import and uses of asbestos and products containing asbestos in Canada, with limited exclusions,” an analysis statement on the government’s website explains.

“The challenge is it takes a long time to develop. So even with the ban on asbestos we’re going to be seeing cases for a very long time,” Demers said.

No safe level of exposure

Even a short period of asbestos exposure can increase the risk of developing mesothelioma and the World Health Organization warns there is no safe level of exposure.

This means firefighters need to take precautions to limit exposure and mitigate risk to stay safe on scenes where asbestos is, or might be, present.

Dan Santoli, WSIB representative for the Hamilton Professional Firefighters Association, said the International Association of Fire Fighters is on top of the issue and that reducing exposure is “the first line of defense.”

“That’s what we’re doing in Hamilton right now and that’s what the IAFF has been pushing for the last four or five years,” Santoli said.

Hamilton – after the fire

“The risks associated with that are primarily after the fire has stopped, when people may be less protected,” said Demers.

Following the St. Peter’s fire, any Hamilton firefighters that had insulation on their gear were rinsed off immediately to reduce further asbestos exposure risks.

“That’s what we did at the St. Peter’s fire. We ensured that any members that had a lot of insulation on their gear, that was rinsed off,” Santoli said. “[Firefighters] that were covered in insulation were rinsed down right on scene.”

Firefighters are to “land and leave” wearing their SCBA, he said, with it on during the entire process.

“If you’re dealing in an area with asbestos, or an area where you might think there is asbestos, they key to it is to keep all your protective equipment on, gloves, flash hoods, bunker gear, your mask – your mask should never, ever come off because asbestos fibres are so small that breathing them in they embed into the lining of your lungs and that’s where you get either mesothelioma or asbestosis.”

Santoli said the department’s health and safety committee has pushed to get an extra set of gear for every firefighter. Each member now has two sets of bunker gear, two flash hoods and two sets of gloves. Each fire station also has its own extractor to clean dirty gear when crews return from a call.

“Once a guy goes to a fire he’s to come back to the station, throw his dirty gear in the extractor, put his clean gear on, take a shower, change into fresh clothes,” Santoli said. “Because if you go to another fire that night you are putting on clean stuff, it’s not the stuff you just came back in that’s soaked in soot and asbestos.”

“The key is if you’re covered in debris from the fire take your gear off with your mask on or wash yourself down. If you wash yourself down, a lot of times the fibres will just wash down off of the gear.”

Santoli said that majority of Hamilton firefighters clean their gear and abide by these procedures like it’s second nature.

“I see that when they come back from a fire the first thing they do is they throw their bunker gear in the extractor and they get it cleaned,” Santoli said. “When you embed it in a new hire, they take that and continually do it for the next 30 years of their career.”

About half of the department’s 530 members have less than seven years experience on the job each.

“Thirty years ago, we would go to a fire, come back and start eating a meal – you wouldn’t clean. You’d have soot on your face and on your hands,” Santoli said. “Well that’s all being pushed aside now.”

“Cancer isn’t gone yet, but I think you’ll see the numbers start to decline as more and more of the new recruits use these new reducing exposure techniques.”

Today, fire departments across Canada are focusing on firefighter health and safety, and this includes asbestos exposure prevention and reduction techniques. Although not every department’s methods are the same, any efforts to reduce exposure will go a long way in fighting asbestos-related cancers.

“Early detection and reducing exposures goes a long way to stopping getting cancer as a firefighter,” Santoli said.

Tips for reducing asbestos exposure from The Mesothelioma Group

- Ensure you have an airtight seal when putting on your respirator. Wear your respirator at all times when on scene.

- Respirators that have a purple HEPA filter or an N-100, P-100, or R-100 NIOSH rating are designed to protect against asbestos fibres.

- Wet parts of the building where firefighters are working to stop fibres from becoming airborne.

- Ensure cleaning supplies, replacement cartridges, and replacement respirators are accessible.

- Wear proper personal protective equipment

- Avoid handling dry dust on scene. Never handle asbestos-containing materials.

- Shower and change into clean clothes after a fire while still on site.

- Ask your supervisor about specialized cleaning procedures, like NFPA 1851.

Lauren Scott is the assistant editor of Canadian Firefighter and Fire Fighting in Canada. lscott@ annexbusinessmedia.com

Print this page