Slave Lake firestorm

By By Jamie Coutts as told to Laura King

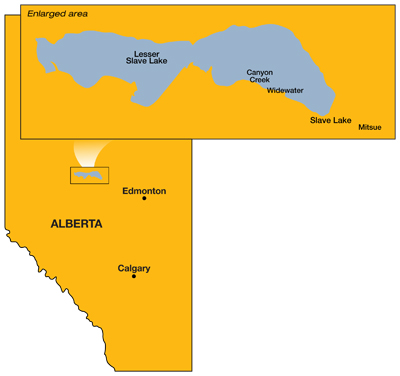

Features Hot Topics Incident ReportsWildfires started burning 10 kilometres south of Slave Lake, in northern Alberta, on Saturday, May 14. Several communities west of Slave Lake were put on two-hour evacuation notice. By 5:30 p.m. a second fire had started east of Slave Lake. Residents of Poplar Estates, Mitsue and the Sawridge Indian Band were evacuated. At 10:30 p.m., the Town of Slave Lake declared a state of emergency. The fires burned for days, claiming 480 homes and countless hectares. Fire Fighting in Canada editor Laura King talked with Jamie Coutts, chief of the Lesser Slave Regional Fire Service, on June 21, a little more than a month after the wildfires, as he continued to replace burned equipment. The fire that consumed Slave Lake moved faster, and with more force – pushed by 100-kilometre-an-hour winds – than any other in recorded Canada history. Coutts’ powerful narrative follows.

Wildfires started burning 10 kilometres south of Slave Lake, in northern

Alberta, on Saturday, May 14. Several communities west of Slave Lake

were put on two-hour evacuation notice. By 5:30 p.m. a second fire had

started east of Slave Lake. Residents of Poplar Estates, Mitsue and the

Sawridge Indian Band were evacuated. At 10:30 p.m., the Town of Slave

Lake declared a state of emergency. The fires burned for days, claiming

480 homes and countless hectares. Fire Fighting in Canada editor Laura

King talked with Jamie Coutts, chief of the Lesser Slave Regional Fire

Service, on June 21, a little more than a month after the wildfires, as

he continued to replace burned equipment. The fire that consumed Slave

Lake moved faster, and with more force – pushed by 100-kilometre-an-hour

winds – than any other in recorded Canada history. Coutts’ powerful

narrative follows.

|

| The record-breaking wildfire in Slave Lake, Alta., in mid-May, burned a third of the town – including the fire department’s sign – but firefighters saved far more than they lost. |

It all started on Saturday, May 14, in the afternoon. At around 1:30, I got a text from a friend who said he saw a fire down the hill from where he was at the ski hill, 17 kilometres south of Slave Lake. I passed that on to SRD [Alberta Sustainable Resources Development] and they started to look into it. I could see a smoke column rising.

We decided that SRD would take that call and I would page in all the duty officers for the Lesser Slave Regional Service. In 2008 we had a pretty decent fire burn through, so we’re pretty gun shy, and we decided to bring in the [chief administrative officers] CAOs of the town and region – MD 124 Lesser Slave River – and start some kind of process.

|

|

| More than 140 Calgary firefighters – some of whom are shown reflected in the pump panel of one of Edmonton’s engines – were among those who joined the Slave Lake firefighting effort in mid-May. |

|

|

|

| Jamie Coutts, chief of the Lesser Slave Regional Fire Service, presented Calgary Deputy Chief Len MacCharles with a “fire ninja” ball cap during a ceremony on June 20. MacCharles acted as incident commander during the wildfire in Slave Lake in mid-May.(Photos by Rob Evans) |

While we were waiting for the CAOs, SRD asked us to go and deploy a bunch of sprinkler kits to two areas, Bayer Road and Gloryland [Estates] – a subdivision south of Slave Lake – and we started to sprinkler those two areas. We got a bunch more calls and had a bunch of people out working, then we got a call for fire out by the airport; we had held back one crew and we sent them to the airport.

While we were down in the [truck] bay looking out to the east – which is the way our doors open – this huge column of smoke went up in Mitsue. The only people left in the hall were myself and my son who is a junior firefighter, so we took the last truck – the third-line pumper – and started heading to the Mitsue area. The guys who were at the airport diverted from that call and headed out to that column as well. They got there first and we took a separate road and tried to spray what we could, but the winds were high and the fire was pushing into Poplar Lane in Mitsue. We left some trucks there to head to the flanks of the fire, and headed to Poplar Lane to start evacuating the Mitsue area – there were RCMP, peace officers and us doing the evacuation.

At about that time I had called SRD to ask about the fire and they were getting a plane in the air to assess the situation. It was that time of day when it’s crossover – low relative humidity and high heat – so this thing was just cooking through the forest, and it wasn’t like we had time to talk to people, it was “Get out of your home, now,” and it was hard for people to wrap their heads around that. We had a really hard time evacuating people.

Once we got them evacuated, we started fighting the fire, but we couldn’t get ahead of it and we pulled everyone out. It blazed through that residential area for five hours. So we went through a back road and tried to catch up to the back of the fire, and SRD went in and tried to back burn. We fought fires at 10 structures that had been burned that first night, and we saved probably another 10 just by being out there. Through that night, there were SRD crews, the fire department and SRD contractors working the fire; we came back [to Slave Lake] in the morning at 6:30 or 7 to regroup and start figuring out how the day was going to turn out. We had sent half our crew home to sleep, so those guys came back, and basically nobody went home to bed.

We spent the rest of the day sprinklering – the fire that was southwest of the town had grown and people were talking about it over-running the towns of Widewater and Canyon Creek. We started helping SRD sprinkler those areas while still fighting fires out in Poplar Lane.

|

Through that day, we had unprecedented support form the public – people were dropping off socks and Gatorade and food and Band-aids – we don’t always get that kind of support so it was pretty overwhelming.

The smoke column south of Slave Lake was fairly small – we were finishing at Bayer Road and Gloryland and Canyon Creek and Widewater – then at 3 p.m. I went to the EOC briefing – they talked about it being a small fire right now and they were working it with planes and helicopters and it seemed manageable; then at 3:30 my phone started to ring off the hook. On my way [out of the EOC] the reeve said the tourist booth one kilometre east of Slave Lake was on fire and we had to evacuate the MD [municipal district] office because it was going to be burned out; within half an hour, the whole outlook on the fire had changed. We went out to the tourist booth and it was being overrun. We recalled all the crews back to Slave Lake from everywhere and told them to set up on 13th Street and 12th Street – these were the last boundaries for us, with the highway and forest from there. We talked about how it was going to get hot and rough and to watch out for people evacuating – at that point our biggest fear was that someone was going to get run over by people evacuating. So we hooked up to hydrants and we started spraying houses. At 4 p.m. it already seemed like it was night – we were smoked in. It was like being in an oven and being sandblasted at the same time.

While that’s going on, the RCMP, SRD, and Fish and Wildlife – they’re all evacuating the southeast part of town and the fire department just set up for what was coming. Once it hit, there were multiple homes on fire at the same time, multiple hot spots. The SRD guys came back in and started hitting those, the fire department was hitting everything they could with their six trucks. There were too many hot spots and it was moving too fast. I left one neighbourhood where there were probably a dozen homes on fire. The water intake was on fire; six, three-storey apartment buildings were on fire; the town office and government office was on fire; and the hospital was being threatened, so we had to make that call to defend the hospital and let the other ones go. There were 50 calls and six trucks so . . .

Our power was out and our water plant has no backup, so water supplies were dwindling. The wind was measured at 100 kilometres an hour and was being sustained. It was like being in a fire tornado. That fire was measured as the 100th percentile – there has never been a fire in Canadian history that moved as fast, and with as much force, in such a short time [according to the SRD].

For me, in a 20-year career being surrounded by a forest fire and having our community threatened dozens of times – Slave Lake is a defend-in-place community; we have the lake on one side, a huge opening on the other side and winds that never get to this – we’ve always had bomber and helicopter supply from SRD. But all the bombers were grounded at 7 p.m. due to wind. And there’s our six trucks and guys, and we’re into 36 hours straight now.

So from there, we put out an all-call through our dispatch system and asked for anyone within 200 kilometres of Slave Lake to respond as best they could: We said, our town is on fire and we’re not going to be able to put it out without help. They dispatch for 33 fire departments – I said call them all and see who will come. At the same time, the EOC put out a call to the province and the province was sending in unbelievable resources. The first resources arrived at about 10 p.m. from out of town, and they basically got tasked into wherever the hot spots were at that time; the first crews went into the north part of town, where we were using bulldozers to hold the line.

Fire Fighting in Canada did a story [in December 2009] after Kelowna burned up and [Kelowna Assistant Chief Lou Wilde] talked about having to choose this house or that house [and having to make the decision to let some burn], and I credit that article for helping me understand that we had to do something different than we had ever done before; we had to send Cats and excavators into neighbourhoods to knock down burning houses – and I want that to be in this story for the next guy who is in my position, so that when it’s like this and everything is different, you have to know that when you’re in that position it’s OK to make those kinds of decisions . . . I 100 per cent credit that article with helping me understand that.

That stopped the head of the fire – but to use a Cat in a neighbourhood to knock down houses and put in fire lines and smash down trees, when you’re an urban fire chief you just can’t get to that point, mentally, without having had some help from someone who had been there before . . . Out in our rural areas, I’ve worked that process before but not in an urban setting.

As these resources started to come in, timing was everything; some got there and helped save one of the schools in the northwest. Some helped with the Cat guard through the town office and the mall – we drove a Cat through the middle of that and reinforced that line. Some got here in time to stop the spread of fire in the southeast, which was the most heavily damaged. Even the Telus building caught on fire, so we had to put that out or communications would have been lost. At about the same time, the fire is getting into Widewater and Canyon Creek, and the water plant was threatened, so we had to get that put out. Houses were burning down at the same time that the Widewater fire hall burned down, and the firefighters were there and pulled out whatever they could and moved on to the next house.

* * *

Through all of this, seven of our firefighters lost their homes, and they all knew that their homes were gone but through the night they never took their foot off the gas . . . So when you talk about the courage of a volunteer firefighter . . . I was a volunteer firefighter for a long time before I was a career firefighter, but that’s the stuff that amazes me. In honesty, for most of us, we were all working in different parts of town and the smoke was incredible and you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face; I would safely say that 70 per cent of us thought our homes had burned but there was no time to find out.

When we were on 12th and 13th streets, we took a time out and everybody was to contact their families and find out where they were and if they couldn’t they were to leave the line and go find out where they were. Texting was still working really well. A lot of them sent their families to the fire hall. It was like the Alamo – the last-stand position – and no matter what, their families were going to be safe there. That’s another thing about firefighters – they do some of the most awful things, but you can only do them if you know your family is safe. There were some people who had to leave with their families – some families were too big for one person to handle or there was just too much stress – and that’s OK. That had to happen.

I had 62 people, firefighters from all four of our regional fire halls; the two farthest are 125 kilometres apart and they cover 10,000 square kilometres. They’re spread out. At 7 p.m. we had drawn some lines on a map and had set out some defensive perimeters; we were trying to hold those perimeters and we didn’t want any damage outside those perimeters. I think we lost two homes outside of that, so we did some good work holding those lines. Throughout the night we had one injury that is worth noting – they were knocking tress down with Cats – and [Capt.] Ken Bolan, he said he thought it was a 90-foot tree and it turned out to be a 130-foot tree and it punched him into the ground – he was pretty smashed up. There were more injuries but not serious like this one – just scraped up arms hands and feet – so when people were bringing us socks and Band-aids and we thought they were crazy, they actually knew what they were doing!

Another thing – these guys were all out fighting wildfires in coveralls and wildland gear; their structural firefighting gear never even got put on them until they got back to the hall and went back out – at first most of those guys were fighting in coveralls and shoes or boots and didn’t have all the protective gear on.

From the time [the fire] was on one side of the highway until it was burning the town was half an hour . . . At one point the Grande Prairie dispatcher called our 911 people and said, “I have 31 calls in the queue . . .” These women [in dispatch] are as tough as nails – they never panic – but you could hear it in their voices. It was as bad as anyone had ever seen.

At about 2:30 in the morning, a new IC showed up and some of the Edmonton people showed up and started telling us about huge numbers of people – to this point some of the smaller communities had sent two people or 10 people or a pumper or a tanker – now the masses were going to show up, and they got here at around 3:30 a.m. – people rolled into town and we got some of our people who had been up for 48 hours out of there and got people into areas that we hadn’t even been in for hours, and of course we had to set up a drafting system from the river because the hydrants were ineffective; we got that drafting system going in the river, we got more tankers and wildland trucks into the neighbourhoods, and all the defensive perimeters were being held at the time. So then [the goal] was to close in from the perimeter to the fire and start drawing some smaller perimeters around neighbourhoods that were on fire but needed to be put out.

At that point, we’d been getting our butts kicked for about 48 hours and that was the first time we all talked and said it’s time to stop talking and worrying about all that we lost and start figuring out what we’re going to win back here. It wasn’t until the sun came up that we all started to realize where everyone had been and the areas that everyone had worked on and to understand the damage and know what we had saved rather than what we had lost. Then, the focus from that point forward was, let’s make sure what we saved stays that way at all costs. So it was dig in, figure it out. IC Darryl Reid from Strathcona County – he was working with the fire chief from Spruce Grove and a district chief from Edmonton – and the three of them went to work and started marking off sector areas and making a plan for all these areas, and then we got the call that Calgary was coming with their task force of 144 people and IC [and Deputy Chief] Len MacCharles would be there.

I snuck off and got about an hour of sleep, then when Calgary got there mid-morning, for the IC and the whole crew into the evening, the big thing was to work with them to figure out where we could do overland hydrant systems to figure out how to put out all the smouldering basements; then, every day at 3 p.m., the winds would pick up to incredible speeds and the humidity would drop and the temperatures would rise, so every day we would have to man up to incredible levels to make sure we could put out the hot spots. And you have to remember that while this was happening in town, out in Widewater and Canyon Creek, all those areas are being . . . this whole area was 45 kilometres long and there were dozens of homes being burned in the MD [municipal district]. The [firefighters from] Edmonton, their first 24 hours were basically spent out in the MD fighting house fires and ground fires.

We kept local people embedded in every crew so there was someone who could get an address to or find a water supply – there were people who went 48 hours with no sleep, then got a few hours, then went 72 more with no sleep. I got six hours in the first five 24-hour days, and that was pretty typical.

What you learn is that the body can take an unbelievable lot of abuse when it has to. Our eyes were all red like a fire truck. There was no power, and no gas, so for four days no one had a shower. In most of the areas, the firefighters would go to the hotel – and would let themselves in – and go to their assigned room in the dark, sleep, and then they would come back with no shower and go back to work. And as the days progressed ATCO Electric and ACTO Gas got power and gas and we hauled a shower shack in beside the fire hall and Wednesday night at midnight was the first shower – I thought I had a pretty good tan going but it all washed off!

On Wednesday [the EOC] gave us lists – to get people back in town this is what each agency has to do. The lists took up a whole wall in a conference room. So everybody got a list – this is what the fire department is going to do, this what public works is going to do – everybody got their list.

In the media it was all very negative – the town had burned down and what are these people are going to do? So the fire department said we are going to put the message out to these media that want to do just negative news, and we’re going to talk about how much is left and how much we saved. We’re going to do Facebook and YouTube and we wanted to get out the message that we saved as much as we could – businesses, critical infrastructure – we just have to get it to the point that we can get everyone back into town. Miles and miles of fencing had to be put up. Every basement had to be excavated and scraped down to get the fires out. There were more than 480 houses burned in Slave Lake and the MD.

Every day you could get these crazy winds and hot temperatures and we would have flare-ups in the MD and we had to stop any more houses from being lost out there. By then, the firefighters were very committed to zero losses. We lost our last house on Tuesday and by then everybody was committed to no more losses, and if there’s a puff of smoke we’re sending 10 trucks – I think at that point there were 30 rigs and 300 firefighters.

Edmonton and Calgary were doing 12 on and 12 off; the smaller departments were 12- or 14- or 16-hour days, whatever it turned out to be. During the day we were really hammering it; the new ICs had set up straight teams – there would be eight trucks sitting out at Canadian Tire on the highway and they would just get dispatched out for whatever was going on; our local and Calgary dispatchers handled it because we lost Grande Prairie dispatch in all this.

I went to one meeting inside the fire hall – about 30 firefighters would be a big meeting for us – and one night there was 200 listening to a briefing. Two-hundred firefighters sitting there and you could have heard a pin drop – they all wanted to hear what SRD wanted to say; they needed to know that things were going better.

We finally all worked through our lists and then got a call that everybody has to send a representative to Main Street in Slave Lake for the big announcement. It was so surreal – there were no street lights at night, no kids yelling and screaming, no dogs barking, no sounds except the people who were working – so there were a few hundred people in a town where there used to be several thousand, and the focus is just get the people back.

From the start of the fire until the first wave of people were allowed back was two weeks – we had been told it would be six weeks, then eight weeks. Everybody just drove themselves into the ground to get the people back. That was all that mattered.

We set up our huge ladder truck with our 30-by-50-foot flag and watched people come back into town. That was huge for us. There wasn’t a dry eye in the house.

Parkland and Peace River were last crews to go home; we had a tiered response by the third week – the volunteers were working nights and the others were covering days. On the Friday of the third week after the fire, Parkland and Peace River went home – and that day it snowed, if you can imagine. In the first 24 hours after returning to normal we responded to six calls – car accidents, flare-ups – it went back to usual.

And everywhere else in the world, a Slave Lake forest fire didn’t burn down their town and if people hadn’t read newspapers or seen it on TV they didn’t know, so salespeople would call and people were going about their business and I would get e-mails asking why I hadn’t replied or returned calls. It was very weird . . .

Over at the EOC – we actually went to them and said we’d had enough of the negative media and asked how we could flip this around. We were sick and tired of watching our town on the news and them saying everything’s lost and we had no hope, and we didn’t want that. As a group of firefighters, we said let’s change the message, and everybody went about that in their own way; lots of guys hit Facebook and Twitter, and we went to the EOC and said, can you help us out with some positive messages? We’d been asked hundreds of times to be interviewed but there wasn’t time, and we decided that this was going to go on for weeks and we just had to make time. [Coutts took time with government PR people to make videos praising his firefighters and all emergency responder and services.]

Personally, we’re back at ’er. There are lots of decisions to be made as a fire chief. I was busy trying to make sure the health of the firefighters was being looked after. My 15-year-old son worked every day through this with us. My wife works in HR for the town; our 11-year-old daughter helped to take care of animals and the firefighters who came in. The fire chief’s job is to look out for everybody, and that didn’t change. It’s just busier now.

Lessons learned – well, that will come. Having a 300-person fire department before the fire comes would help!

We’re going to have to pre-plan this area a lot more carefully now. We never thought this could happen – Slave Lake was a defend-in-place community but we couldn’t do that. This won’t be our last forest fire; this won’t even be our last forest fire this year, so we have to find a way, quickly, to take care of these areas. We’re going to have to work more closely with SRD – we already had a good relationship. We’re going to have to make sure that our new equipment that comes is more user friendly and adequate. We need back-up power in our critical infrastructure – water, fire halls. Our EOC burned down so we need to figure out where the EOC is going to be and how to manage that.

We had had a 70 per cent failure rate on our hoses that were used and a 60 per cent failure in our gear, from the heat – holes the size of toonies burned into our hoses. Embers – anything on the truck that had embers land on it was burned. Our gear is fire retardant, it’s not fireproof – so when hot embers land on it, it burns. The reflectors burn off.

This has changed the whole way that our fire department operates. We were always a stay-ahead department – if one truck is good we send two, if two trucks are good we send three, and we can, because it’s regional.

What could we do differently? Nobody expected the wind to be 100 kilometres an hour, sustained. Nobody expected the bombers and the helicopters to not be able to help us. Our community is fed from three areas for power – nobody expected all three to be burned, so we didn’t think it in the realm of possibility to lose all three; we have to get rid of that term – everything is now in the realm of possibility – and we have to develop a whole new possibility of what could happen. We do table tops just like other departments – we take things to the extremes – but in our table tops, this was never in the realm of possibility.

The biggest lesson learned is we have to plan farther – when you’re in wildland areas the world is changing, the weather in the world is changing, and we have to plan with that change.

That time period for Slave Lake is historically a rainy time. Our town burned down in unbelievable temperatures, then we went to snow and then to flooding. In a six-week period we went from fire to snow to floods. So if people don’t think the weather is changing. . .

There were 700 firefighters from 30 different fire departments that helped out. We couldn’t have done it without all those people.

Print this page