Stress management

By Brant Kiessig

Features Health and Wellness WellnessAn experienced firefighter battling a structural fire is alone in a heavy smoke filled environment. Without warning his SCBA malfunctions and he has trouble getting air. Suddenly, the low-air alarm activates.

An experienced firefighter battling a structural fire is alone in a heavy smoke filled environment. Without warning his SCBA malfunctions and he has trouble getting air. Suddenly, the low-air alarm activates.

|

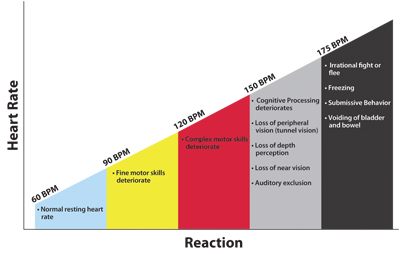

| Graph adapted from On Combat: The Psychology and Physiology of Deadly Conflict in War and in Peace by Lt.-Col. Dave Grossman and Loren W. Christensen, PPCT Research Publications, 2004.

|

In his book On Combat: The Psychology and Physiology of Deadly Conflict in War and Peace, Lt.-Col. Dave Grossman describes typical physiological and psychological responses to the sudden and unexpected deterioration of a situation. The dilemma would increase anxiety. An already elevated heart rate would quickly rise beyond 175 beats per minute. Rational thought starts to dissipate. Appropriate reaction to the predicament becomes difficult. When the heat is on and sudden, unexpected negative changes occur, the effects of acute stress will impact firefighters the same way it affects soldiers in combat.

How can acute stress be recognized? How does it affect decision making? How can firefighters keep from freezing at a critical moment? Can the effects of stress be reduced? Is everybody affected the same way? There has been lots of talk about stress management for first responders but much of it has focused on after-incident, or post traumatic stress. There is plenty of research on the stress that occurs during incidents and Canadian fire departments should understand these findings and adopt the researchers’ recommendations.

The impact of high temperatures

Ambient air temperatures can reach more than 250 C within the fire space. PPE reduces the ability to relieve thermal stress through perspiration. A 2002 compendium of energy/oxygen use for physical activities by Barbara Ainsworth of the University of South Carolina shows that the expended energy in typical firefighting operations equates to the metabolic action of running 12 kilometres per hour (eight-minute miles) at a one per cent incline.

In the late 1990s, an Illinois Fire Service Institute study discovered the average tympanic temperature (measured through the ear) of firefighters completing 16 minutes of activity in an atmosphere varying between 76 C and 92 C was 40 C (normal body temperature is 37 C). Results revealed a reduction in heart stroke volume and increased dilation of blood vessels closest to the skin, causing a dangerous drop in blood pressure.

A 2007 study of physiological stress associated with fire fighting by Indiana University and the Indianapolis Fire Department reported a direct link between firefighter fatalities attributed to stress or exertion and the onset of acute stress symptoms. The assumption is that these LODDs are attributable to acute stress induced cardiac compromise.

Interestingly, the Illinois study discovered that despite thermal stress, dehydration and elevated heart rates, firefighters perceived their efforts during extreme operations to be “hard” rather than the expected “very, very hard”. This response was attributed to impaired cognitive ability. In other words, firefighters could be in heat distress and not realize it.

|

| Lt.-Col. Dave Grossman’s book On Combat: The Psychology and Physiology of Deadly Conflict in War and in Peace and its messages about stress are applicable to the fire service.

|

When encountering extreme temperatures, firefighters must maintain situational awareness while engaging in strenuous physical activities. It is accepted that individual response varies due to age, experience and overall health and fitness but there are a number of presumptive measures that can help to alleviate heat stress.

Advances in technology have resulted in PPE with a high degree of protection from flame and thermal insult, while still providing some metabolic heat dissipation. They are lightweight, durable and allow flexibility. In order for this equipment to work it must be worn, cleaned and maintained to manufacturer specifications. Dirty equipment is no badge of honour.

Maintaining proper hydration before, during and after firefighting operations helps to alleviate heat-related stress. The American College of Sports Medicine released an article in 2003 containing research on hydration. It suggested that to properly re-hydrate, it is necessary to ingest 150 per cent of water weight loss after physical activity, coupled with increased sodium intake. It was noted that most commercial sports drinks do not contain appropriate levels of sodium and suggested augmentation with sodium-rich foods such as pretzels and pizza.

It’s important to recognize that metabolic heat build up occurs during fire operations. Rehabilitation, with an accompanying two-bottle policy (automatic rehab after two SCBA bottles are used), even in cold weather, will keep crews fresh and reduce heat stress. A 2006 study by the University of Manitoba showed that immersion of forearms and hands in 10 C and 20 C water effectively reduced core temperatures.

Better levels of health and fitness would help to minimize stress effects on firefighters’ hearts and other physiological functions; we’re not talking Olympic athlete here, just a regular regime of balanced cardio and strength fitness. (For more information, see the story Standard operating procedures in the October 2009 issue of Canadian Firefighter and EMS Quarterly.)

If the SCBA comes equipped with a thermal alarm understand its parameters. What information is it giving?

Evaluate the need to be in the high heat areas. Would proper ventilation, positive pressure attack, transitional attack or other exterior techniques reduce fire space temperatures?

Stay current on offensive hose stream techniques and equipment avoiding situations that force enduring more heat than necessary.

Wear appropriate garments under the bunker gear. Some departments have fatigue clothing that is required to be worn. Hopefully it is made of lightweight Nomex or some natural fibre. Some firefighters are wearing space-age polyesters that wick moisture under their station wear. These were never intended for firefighting operations. Synthetics melt against the body during a high heat intrusion. Witness the agony of a burned firefighter having melted synthetics removed and discussion on the matter will likely cease.

While firefighters experience the effects of metabolic heat buildup, the Illinois study found anxiety induced increase in heart rate and also impaired cognitive ability. Understanding the body’s nervous system explains this phenomenon. It is made up of the somatic system (responsible for voluntary muscle action) and the autonomic system (responsible for automatic functions) which will be the primary focus of the explanation of the physiological effects.

The autonomic system is further divided into two directionally opposing systems. The parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) is responsible for everyday bodily functions at rest such as bladder control, bowel control and slowing the heart rate. The other is the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). We’ve all heard the saying “that scared the crap out of me”. When subjected to high stress situations such as a sudden unexpected event (flashover or collapse) or extreme anxiety (lost in a building or running out of air) the brain’s alarm system releases a burst of adrenaline that switches the body to the SNS from the PNS. It prepares for fight or flight. The pupils dilate to enhance vision, the heart rate increases to move greater quantities of oxygen to the large muscles and peripheral circulatory system constricts to reduce bleeding if cut. When resources switch to the SNS, the PNS is effectively shut down, resulting in potentially uncontrolled bowel movements or urination.

The most important effect of SNS primacy is the increase in heart rate. Figure 1 shows five levels of anxiety, progressing from white (normal resting heart rate) through to black where irrational fight or flight, freezing or submissive behaviour occur. Stress-induced heart rate increase is not synonymous with increases due to physical activity and no conclusive analysis is available on the cumulative effects.

The U.S. Firefighter Disorientation study released in 2003 by the San Antonio Fire Department examined the role of a firefighter becoming disorientated and its connection to firefighter fatalities. In 100 per cent of the cases studied, sudden changes from manageable situations to a feeling of being overwhelmed or loss of control of a situation led to a surge of the SNS reaction, resulting in the firefighter moving to the black zone very quickly. Firefighters effectively freeze, become incapable of rational thought or display the submissive behaviour of curling up in a ball and hoping the threat subsides.

This becomes a life-threatening scenario for a firefighter who is lost, trapped or facing a sudden or unexpected deterioration in his situation. An officer or incident commander who suddenly feels out of control or overwhelmed will react in the same negative manner. There are some measures that can help to control the fight-or-flight response.

- Don’t panic. Learn to recognize the onset of personal panic symptoms. Tactical breathing is effective at combating stress. Inhale deep belly breaths through the nose to expand the stomach like a balloon. Do the following four steps to a mental four count and repeat four times.

• In through the nose, two, three, four.

• Hold two, three, four.

• Out through the lips two, three, four.

• Hold two, three, four. - Maintain good sleep habits. Seven to nine hours of uninterrupted sleep is beneficial for body maintenance and mitigating stress effects.

- Immediate Action Drills (IAD). Police and military personnel train in drills that don’t require cognitive function when a life-threatening event takes place. Training comprises practising an evolution hundreds of times to make the response automatic. Firefighters should train in mayday evolutions or survival techniques so the action will engage automatically when the SNS is triggered. Many firefighters believe they have the experience to think their way out of a situation. Remember, cognitive ability is severely impaired. Have the IAD get you out of harm’s way until you can recover some cognitive function.

- redicting precisely what will transpire at a response is difficult; however, mental rehearsal of simple functions will refresh the memory. Visualize the task, forecast potential problems and formulate various actions that would give a positive result.

- Ensure a thorough understanding of department SOPs, including the incident command system, personnel accountability, RIT and other specific departmental procedures. From firefighter up to incident command, stress can be alleviated by understanding what’s in place at responses and how they are to be used.

- Implement a close calls committee. Investigate close calls within the department. Critique these events to identify possible deficiencies in operational SOPs or required increase in training or education. Lives may depend on it.

These measures pertain to fire responses; however, they can be adapted to apply in all emergency situations.

Capt. Brant Kiessig joined the Thunder Bay Fire & Rescue as a professional firefighter in 1983. He is a certified trainer/facilitator, a certified Community Emergency Management Coordinator, a rope rescue technician, a member of TBFRS high angle rescue team, a certified NFPA 1670 & 1006 trench rescue technician, a member of the TBFRS HUSAR team, an auto extrication instructor and the 2001 over-40 national FireFit champion. Contact him at firewarrior3@gmail.com

Print this page