Up in smoke

By Canadian Firefighter

Features Hot Topics Incident ReportsWhen Sooke Fire Chief Steve Sorensen was contacted by the local RCMP in late December, the call for assistance was unlike any other the 27-year department member had received.

When Sooke Fire Chief Steve Sorensen was contacted by the local RCMP in late December, the call for assistance was unlike any other the 27-year department member had received.

|

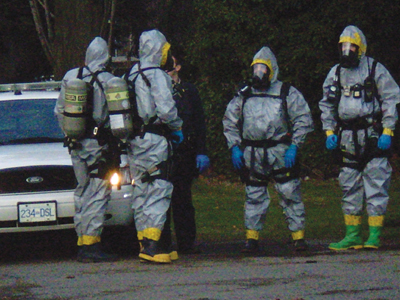

| Four members of the RCMP clandestine lab team who responded to an incident in Sooke, B.C., just before firefighters moved in for a “raid” on an alleged drug operation that turned out to be perfectly legal.

Photo courtesy Sooke Fire Department

|

Sooke RCMP Staff Sgt. Stephen Wright doubted he could secure a search warrant to investigate a suspected illegal drug lab. But as concerns about public safety mushroomed, he decided to enlist the services of the 45-member volunteer Sooke Fire Department, which serves roughly 12,000 residents in a rural/urban area about 30 kilometres west of Victoria.

“We did not have enough information to obtain a search warrant,” Staff Sgt. Wright says. “We felt it was prudent to check it out.”

Following Staff Sgt. Wright’s decision, an operation was set into motion for a surprise descent at a trailer park that had seen better days but not likely such a show of police force.

Joining Sooke’s 10 volunteer firefighters was a four-man specialized clandestine lab team from Vancouver, a five-man emergency response team and police dog and handler from Victoria, and five Sooke RCMP.

All of them were acting on the suspicion that a clan lab, with its inherent dangers to both the trailer park residents and emergency responders, was producing some sort of illegal drug.

The joint firefighter/police operation, large by Sooke standards, required surefire organization. “Our plan was that we go in under the Fire Services Act, ask the property owners if they would let us look at the property to determine if it was a hazard. If it became a criminal matter, the RCMP would take over and get a search warrant,” explains Chief Sorensen, 49, who took over the department’s top job in June 2009.

Under Section 21 of the Fire Services Act of B.C, following a complaint, a fire commissioner or fire inspector can enter any premises, anywhere in B.C., if there is suspicion that a fire hazard exists on the premises.

In addition to Chief Sorensen, the Sooke department has three paid, full-time members. Roughly 40 per cent of department calls are medical-related, 20 per cent are for MVAs and five per cent are fire calls.

According to Staff Sgt. Wright, police in B.C., and even across Canada, regularly ask fire departments for their help to investigate clandestine labs when search warrants can’t be obtained. He said fire departments’ training for hazardous materials is invaluable to the police. Members of the Sooke Fire Department are no exception.

Yet this “tag teaming” is being slammed by the B.C. Civil Liberties Association.

“You’re doing through the back door what you can’t do through the front door,” says Micheal Vonn, a policy director with the Civil Liberties Association. “We don’t want to see legitimate safety concerns used as a means to circumvent warrant procedures.”

|

| The Sooke Fire Department and RCMP are urging Health Canada to make fire and police aware of registered medical marijuana sites.

|

The separation between policing and safety should be maintained, says Vonn from Vancouver. The two agencies have different responsibilities and merging them could pose risks in many areas, she says.

But an exhaustive amount of information is needed to convince a B.C. judge or justice of the peace, beyond a reasonable doubt, that premises should be entered by police, maintains Staff Sgt. Wright. Background checks, recent activity at the suspect premises and specific information about the suspected crime are needed.

Suspicion alone isn’t enough, says Staff Sgt. Wright, who arrived in Sooke late in 2009 from the Whistler RCMP detachment. “We can’t enter a residence even if someone reports they’re making bombs,” he says.

To build their case, Sooke RCMP began collecting evidence following a complaint to the RCMP of a chemical smell in the roughly 25-trailer park. During a drive around the park, the police spotted several antifreeze containers and propane bottles on the suspected property. Reports of suspicious activity were also received, Staff Sgt. Wright says. The Sooke Fire Department also got a complaint about “strange odours” in the trailer park, says Chief Sorensen.

Within days, the police decided to act and on the morning of Dec. 23, after police and firefighters were in place, a plan was mapped. Soon after, Chief Sorensen and his training officer, Capt. Matt Barney, donned bulletproof vests, a first for both of the fathers.

“I was doing OK until they gave me the bulletproof vest and then the danger of it kind of sunk home,” recalls Chief Sorensen. Going into the operation, Sorensen and Barney initially thought it would be a rather casual event, not the full-on undertaking it became.

“It almost looked like a parade. There had to have been a dozen police and fire vehicles. It’s not unusual to see Mounties with sidearms but when they start showing up with fully automatic weapons and the yellow hazmat team is coming in on the running board of the suburban, it’s straight out of the movies,” said Sorensen of the police who remained hidden from the trailer residents. “They were all over the place. If somebody ran they were trying to cover the bases.” Sooke’s firefighters were also hidden from view, with adrenalin pumping, prepared to spring into action.

As the two fire officers approached the aging trailer, a few steps behind were two plainclothes emergency response team members, ready to take over if it became obvious an illegal operation was found. Coincidentally, there had been a fire, believed to have been started by discarded cigarettes, at the same trailer several years ago, Chief Sorensen recalls.

An older woman answered the door and soon after her middle-aged son joined her, bearing documents from Health Canada that stated he could grow medicinal marijuana on the premises. A doctor had prescribed marijuana as a way for the man to treat his chronic pain. With the revelation that the suspected clan lab was actually a legal marijuana patch, the “air went out of everybody,” Chief Sorensen admits.

Eager to show his unexpected visitors his legal grow op, the male occupant led Sorensen, Barney and the two plainclothes police to his three-metre by three-metre cedar shed as the clan lab team, the German Shepherd and rest of the operation continued to hide nearby.

Inside were about 30 young marijuana plants. The man’s Health Canada licence allowed a medicinal marijuana garden of up to 97 plants. “He was very proud of what he’d built,” say Chief Sorensen. Also a journeyman carpenter, Chief Sorensen was impressed with the well-constructed shed that contained a smoke alarm and charcoal air filter. “We didn’t smell anything when we got there so I don’t know what people were smelling before,” he says. The man and his mother did not face any charges.

Local taxpayers will pay the substantial cost of the pre-Christmas strike, Chief Sorensen estimates. (The Vancouver-based clan lab team had to travel on B.C. Ferries from Vancouver.) And at a debriefing session later that day, the police and fire responders “felt a bit silly,” about how the surprise visit played out. “Did we do the right thing?” Chief Sorensen wonders. “Now the police are worried that because we went in like this, the neighbours know and the neighbours talk. Say they’ve observed something going here and elements put two and two together. So I think you’ve actually put the guy in more danger by doing it this way.”

Staff Sgt. Wright’s view is that public safety for the entire neighbourhood outweighs concerns for the individual in whatever activity is presumed. He would employ the same strategy again if necessary to safeguard the public.

But the bigger issue that emerged from this event is that fire and police departments in B.C. are not told by Health Canada where registered medical marijuana sites are located. Health Canada fears that if the information were released, criminals would find out and break into legal marijuana operations.

Currently, if local authorities suspect a property has such a site, they contact Health Canada with the address and Health Canada either confirms or denies a medical marijuana site at that address.

In January, the District of Sooke’s Protective Services Committee, which includes the Sooke Fire Department, Sooke RCMP and Building and Bylaw Services, asked that Sooke Council send a letter to Health Canada. The agencies want Health Canada to tell police and fire departments where registered medical marijuana sites are located. They maintain the information would be safe with them.

“There’s brand new medical marijuana grow ops all over the place,” says Chief Sorensen. “They don’t have to tell the police or anyone in the community.”

His fear is that, while legal, they may be shoddily built and carry with them all of the hazards of an illegal marijuana grow op. “It’s a safety issue. If we don’t know what’s there, we don’t know what we’re dealing with. Just because they have a licence, it doesn’t mean it’s safe.”

Chief Sorensen’s final impression of the December event: he isn’t sure when he’ll load on a bulletproof vest again.

Print this page