Learning from fire death data

By Len Garis and Mandy Desautels

Features Hot Topics10 years of coroner data reveals factors behind escalated Indigenous fire risk in Canada

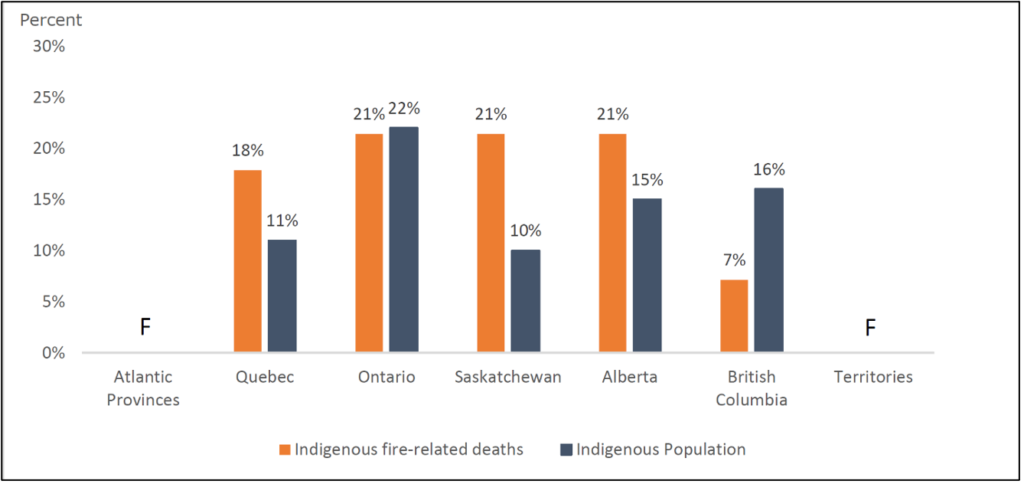

This graph compares the proportion of fire-related deaths among Indigenous people to the region’s Indigenous population percentage, with estimates for the Atlantic Provinces and the territories removed due to sample size limitations. Image Credit: Canadian Coroner and Medical Examiner Database and Statistics Canada.

This graph compares the proportion of fire-related deaths among Indigenous people to the region’s Indigenous population percentage, with estimates for the Atlantic Provinces and the territories removed due to sample size limitations. Image Credit: Canadian Coroner and Medical Examiner Database and Statistics Canada. A new study of Canadian coroner data suggests that unsafe homes, lack of working smoke alarms and lack of attention to correcting major housing repairs needed are among the factors in why Indigenous people in Canada die in fires more often than non-Indigenous people.

The National Indigenous Fire Safety Council (NIFSC) has released a new Statistics Canada study delving into the circumstances surrounding fire deaths in Canada from 2011 to 2020, based on the Canadian Coroner and Medical Examiner Database (CCMED) and Canadian Vital Statistics death data.

Titled Circumstances Surrounding Fire-related Deaths among the Indigenous People in Canada, 2011 to 2020, the report was commissioned by NIFSC, which is funded by Indigenous Services Canada. The study not only reinforces earlier research showing that fire-related deaths and injuries are significantly higher for Indigenous than non-Indigenous people but sheds new light on the contributing factors.

The study data suggests that Indigenous people are four times more likely than non-Indigenous people to die in a fire in Canada, and that the risk is highest for those who live in rural areas with underfunded fire services, in homes that need major repairs, and in provinces without ongoing and widespread smoke alarm education and installation programs.

“Study after study has shown us that Indigenous people in Canada die in residential fires at a much higher rate than non-Indigenous people, but this new data helps fill in the gaps as to why that is happening,” said Blaine Wiggins, senior director of the NIFSC. “With this compelling new evidence, we urge decision-makers across Canada to acknowledge the factors that increase this risk and to take immediate and appropriate steps to address them.”

Study Approach

Fires are the fourth most common cause of unintentional death and injury worldwide. In Canada, an average of 220 people died in fires each year from 2011 to 2020.

A total of 2,200 deaths were reported to the CCMED during that time frame, but the study sample was about one-third of that number, limited to 700 deaths that could also be linked to the 2006 and 2016 long-form censuses and the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS) in order to select people who identified as Indigenous and gain valuable location information.

While the study sample may not represent all fire-related deaths in Canada, the study’s key findings are based on data that was consistent between the sample and the total fire deaths: place of death, sex and age. It should be noted that the number of deaths reported maybe lower than expected because only closed cases are published in the CCMED.

Key Insights

Key results related to individual risk are as follows:

- Indigenous people made up 20 per cent of fire deaths from 2011 to 2020 but, based on 2016 Census data, represent 4.9 per cent of the total population.

- Indigenous people who died in fires were on average 41 per cent younger than non-Indigenous people (mean age of 39 versus 59). This may be explained in part by their younger age profile; 83 per cent are under age 55 compared to 69 per cent for non-Indigenous people.

- Alberta, Saskatchewan and Quebec had the highest proportion of Indigenous fire deaths based on their Indigenous populations, while Ontario and British Columbia had the least.

Results related to the circumstances surrounding to fire deaths are as follows:

- For both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, most fire deaths occurred in residential fires, most often in a single-detached home and in the winter. Fire deaths were more prevalent among men than women for both groups.

- Indigenous people who died in a fire were 4.5 times more likely to live in homes that need major repairs than non-Indigenous people (about 56 per cent versus 13 per cent).

- Twice as many Indigenous people who died in a fire lived in rural areas compared to non-Indigenous people (two-thirds versus one-third). Rural areas tend to be further from fire stations and paramedic services and served by volunteer firefighters.

- Cooking, electrical and heating devices were the most common sources of fatal fires for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, followed by cigarettes and candles or other open flames. However, ignition sources were less often specified in Indigenous fires. This may point to a reduced level of fire service in rural areas, either related to data collection or response times that resulted in damage too extensive to identify the source.

- Nearly one in eight (12 per cent) Indigenous fire deaths were reported in homes without a working smoke alarm, similar to non-Indigenous people. Noting smoke alarms was either not specified, unknown or not applicable for 80 per cent of fire-related deaths among Indigenous people.

The risk factors for Indigenous people are combined with other known vulnerabilities that increase the danger of fire-related injury and death, including lower education and income, overcrowded living conditions, and limited access to healthcare in rural areas.

Provincial Overview

According to the 2016 Census of Population, the distribution of Indigenous people living in Canada varied by province and territory. While the distribution of fire-related deaths among Indigenous people also varied, it was not comparable to the Indigenous population distribution (Chart below).

The proportion of fire-related deaths among Indigenous people was greater than the proportion of the Indigenous population in Alberta (21 per cent of Indigenous deaths versus 15 per cent of the Indigenous population), Quebec (18 per cent versus 11 per cent), and Saskatchewan (21 per cent versus 10 per cent), suggesting an overrepresentation of fire-related deaths in these Provinces. Underrepresentation was observed in British Columbia (seven per cent versus 16 per cent), where the proportion of fire-related deaths among Indigenous people was 2.3 times lower than its share of the Indigenous population. In Ontario, the proportion of Indigenous fire-related deaths (21 per cent) was similar to the Indigenous population proportion (22 per cent). Fire-related deaths for Manitoba were not available in the linked dataset and death proportions for Atlantic Canada and the territories were suppressed to meet Statistics Canada’s confidentiality requirements.

This graph compares the proportion of fire-related deaths among Indigenous people to the region’s Indigenous population percentage, with estimates for the Atlantic Provinces and the territories removed due to sample size limitations. Image Credit: Canadian Coroner and Medical Examiner Database and Statistics Canada.

Using What Was Learned

The new report provides direction for interventions to reduce the fire risk for Indigenous people:

- Home maintenance: Home disrepair has been identified as a risk factor in fire deaths. Census data shows that 19.4 per cent of Indigenous people live in a dwelling requiring major repairs, compared to six per cent of non-Indigenous people.

- Smoke alarms: Research has shown working smoke alarms significantly reduce the risk of fire injuries and deaths. The provinces with the lowest proportion of Indigenous fire deaths based on population, Ontario and British Columbia, both have ongoing smoke alarm education and installation programs with a focus on vulnerable populations.

- General fire education: In addition to smoke alarms, a report by the Ontario chief coroner has identified that education on topics such as fire escape, fire safety and home maintenance is key to reducing fire fatalities in First Nations.

- Information gathering: Data related to Indigenous-specific fire deaths was lacking in a number of areas and topics. Fire services continue to be encouraged to report data to the National Fire Information Database to support the development of evidence-based interventions.

“This new study has brought important insights to aid in our efforts to reduce Indigenous fire-related deaths and injuries in Canada,” said Michelle Vandervord, president of the National Indigenous Fire Safety Council. “By pinpointing the circumstances leading to fatal fires, we can help ensure that investments in Indigenous fire safety are being directed to the most promising interventions. We would like to see this data translated into tangible actions across the country.”

In terms of future research, potential next steps could involve expanding the study to look into the impact of some of the socio-economic factors (such socio-economic standing, food security, cost of living, overcrowded living conditions and household income), funding for housing structures, the allocation of funds to meet community needs, the role of fire and building codes, and status of home maintenance on fire-related deaths among Indigenous communities in Canada.

The report Circumstances Surrounding Fire-related Deaths among the Indigenous People in Canada, 2011 to 2020 may be viewed here.

Len Garis is director of research for the National Indigenous Fire Safety Council, Ret. Fire Chief (ret) for the city of Surrey, B.C., associate scientist emeritus with the B.C. Injury Research and Prevention Unit, adjunct professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice and associate to the Centre for Social Research at the University of the Fraser Valley (UFV), and a member of the Affiliated Research Faculty at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. Contact him at lwgaris@outlook.com.

Mandy Desautels is senior director of strategic initiatives at the National Indigenous Fire Safety Council (NIFSC), a project of the Aboriginal Firefighters Association of Canada (AFAC). She holds a B.Sc. in global resource systems from the University of British Columbia and a Master of Healthcare Administration from University of British Columbia. Prior to joining NIFSC, she worked for BC Emergency Health Services and prominent NGOs. Contact her at MandyD@afac-apac.ca.